MODERN MONGOLIA--the Mongolian People's Republic--comprises only about half of the vast Inner Asian region known throughout history as Mongolia. Furthermore, it is only a fraction of the great Mongol Empire of the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries that stretched from Korea to Hungary and encompassed nearly all of Asia except the Indian subcontinent and parts of Southeast Asia. Because the Mongol Empire was so vast--the largest contiguous land empire in the history of the world--the Mongols were written about in many languages by numerous chroniclers of divergent conquered societies, who provided a wide range of perspectives, myths, and legends. In addition, because many foreign accounts are about the Mongol invasions and were written by the conquered, the Mongols often are described in unfavorable terms, as bloodthirsty barbarians who kept their subjects under a harsh yoke. Mongol sources emphasize the demigod-like military genius of Chinggis Khan, providing a perspective in the opposite extreme. The term Mongol itself is often a misnomer. Although the leaders and core forces of the conquerors of Eurasia were ethnic Mongols, most of the main army was made up of Uralo-Altaic people, many of them Turkic. Militarily, the Mongols were stopped only by the Mamluks of Egypt and by the Japanese, or by their own volition, as happened in Europe. In their increasingly sophisticated administrative systems, they employed Chinese, Iranians, Russians, and others. Mongolia and its people thus have had a significant and lasting impact on the historical development of major nations, such as China and Russia, and, periodically, they have influenced the entire Eurasian continent.

Until the twentieth century, most of the peoples who inhabited Mongolia were nomads, and even in the 1980s a substantial proportion of the rural population was essentially nomadic. Originally there were many warlike nomadic tribes living in Mongolia, and apparently most of these belonged to one or the other of two racially distinct and linguistically very different groupings. One of these groupings, the Yuezhi, was related linguistically to the ancient nomadic Scythian peoples--who inhabited the steppes north and northeast of the Black Sea and the region east of the Aral Sea--and was therefore Indo-European. The other grouping was the Xiongnu, a nomadic people of uncertain origins.

Although in the course of history other peoples displaced, or became intermingled with, the Yuezhi and the Xiongnu, their activities, conflicts, and internal and external relations established a pattern, with four principal themes, that continued almost unchanged--except for the conquest of Eurasia in the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries--until the eighteenth century. First, among these four themes, there were constant fierce struggles involving neighboring tribes, engaged in frequently shifting alliances that did not always follow ethnic, racial, or linguistic lines. Second, during periods when China was united and strong, trade with Inner Asian peoples was allowed, and nomadic states either became vassals of the Chinese emperor, or they retreated beyond his reach into the northern steppes; conversely, when China appeared weak, raids were made into rich Chinese lands, sometimes resulting in retaliatory expeditions into Mongolia. Third, occasional, transitory consolidation--of all or of large portions of the region under the control of a conqueror or a coalition of similar tribes--took place; such temporary consolidations could result in a life-or- death struggle between major tribal groupings until one or the other was exterminated or was expelled from the region, or until they joined forces. Fourth, on several occasions, raids into northern China were so vast and successful that the victorious nomads settled in the conquered land, established dynasties, and eventually became absorbed--sinicized--by the more numerous Chinese.

Within this pattern, the Xiongnu eventually expelled the Yuezhi, who were driven to the southwest to become the Kushans of Iranian, Afghan, and Indian history. In turn, the Xiongnu themselves later were driven west. Their descendants, or possibly another group, continued this westward migration, establishing the Hun Empire, in Central and Eastern Europe, that reached its zenith under Attila.

The pattern was interrupted abruptly and dramatically late in the twelfth century and throughout the thirteenth century by Chinggis and his descendants. During the consolidation of Mongolia and some of the invasions of northern China, Chinggis created sophisticated military and political organizations, exceeding in skill, efficiency, and vigor the institutions of the most civilized nations of the time. Under him and his immediate successors, the Mongols conquered most of Eurasia.

After a century of Mongol dominance in Eurasia, the traditional patterns reasserted themselves. Mongols living outside Mongolia were absorbed by the conquered populations; Mongolia itself again became a land of incessantly warring nomadic tribes. True to the fourth pattern, a similar people, the Manchus, conquered China in the seventeenth century, and ultimately became sinicized.

Here the pattern ended. The Manchu conquest of China came at a time when the West was beginning to have a significant impact on East Asia. Russian colonial expansionism was sweeping rapidly across Asia--at first passing north of Mongolia but bringing incessant pressure, from the west and the north, against Mongol tribes--and was beginning to establish firm footholds in Mongolian territory by conquest and the establishment of protectorates. At the same time, the dynamic Manchus also applied pressure from the east and the south. This pressure was partly the traditional attempt at control over nomadic threats from Mongolia, but it also was a response to the now clearly apparent threat of Russian expansionism.

From the late seventeenth century to the early twentieth century, Mongolia was a major focus of Russian and Manchu-Chinese rivalry for predominant influence in all of Northeast Asia. In the process, Russia absorbed those portions of historical Mongolia to the west and north of the present Mongolian People's Republic. The heart of Mongolia, which became known as Outer Mongolia, was claimed by the Chinese. The area was distinct from Inner Mongolia, along the southern rim of the Gobi, which China absorbed--those regions to the southwest, south, and east that now are included in the People's Republic of China. Continuing Russian interest in Mongolia was discouraged by the Manchus.

As Chinese power waned in the nineteenth and the early twentieth centuries, however, Russian influence in Mongolia grew. Thus Russia supported Outer Mongolian declarations of independence in the period immediately after the Chinese Revolution of 1911. Russian interest in the area did not diminish, even after the Russian Revolution of 1917, and the Russian civil war spilled over into Mongolia in the period 1919 to 1921. Chinese efforts to take advantage of internal Russian disorders by trying to reestablish their claims over Outer Mongolia were thwarted in part by China's instability and in part by the vigor of the Russian reaction once the Bolshevik Revolution had succeeded. Russian predominance in Outer Mongolia was unquestioned after 1921, and when the Mongolian People's Republic was established in 1924, it was as a communistcontrolled satellite of Moscow.

|  |

Mongolian National Anthem

Mongol Ulsiin Toriin Duulal

lyrics by (ug): Ts.Damdinsuren

music (aya): B.Damdinsuren & L.Mordorj)

Darhan manai huvistgalt uls

Dayar Mongoliin ariun golomt

Daisnii huld hezee ch orohgui

Dandaa enhjij uurd monhjino.

Hamag delhiin shudarga ulstai

Hamtran negdsen egneeg behjuulj

Hatan zorig, buhii l chadlaarai

Hairt mongol ornoo manduulya

Zorigt Mongoliin zoltoi arduud

Zovlong tonilgoj, jargaliig edlev

Jargaliin tulhuur, hogjliin tulguur

Javhlant manai oron mandtugai

Hamag delhiin shudarga ulstai

Hamtran negdsen egneeg behjuulj

Hatan zorig, buhii l chadlaarai

Hairt mongol ornoo manduulya

Sukhbaatar

It wont take long before you wonder who Sukhbaatar is his statue astride a horse dominates the square named after him in Ulaanbaatar, his face is on many currency notes, and there is a provincial capital and aimag called Sukhbaatar.

Born in 1893, probably in what is now Ulaanbaatar, Sukh (which means ax), as he was originally named, joined the Mongolian army in 1911. He soon became famous for his horsemanship, but was forced to leave the army because of insubordination. In 1917, he joined another army, found against the Chinese, and picked up the added moniker of baatar, or hero.

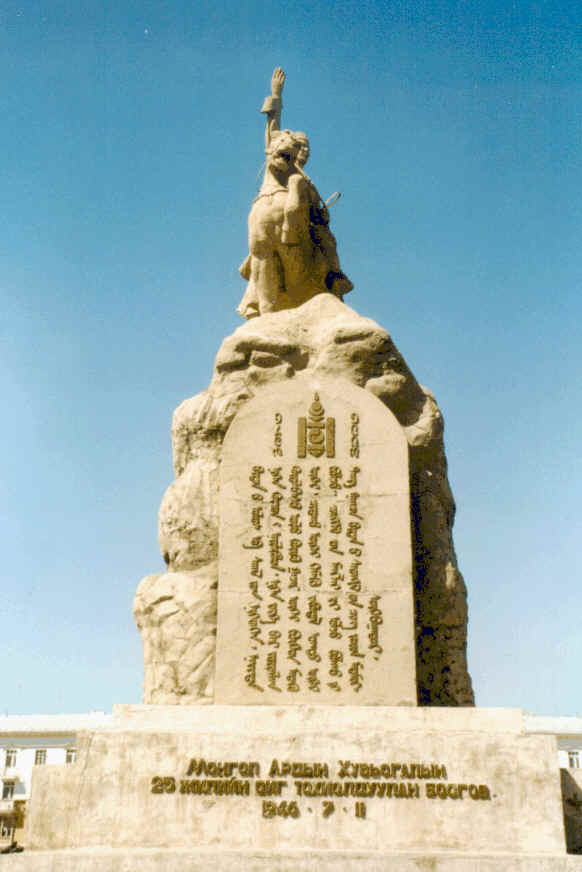

By 1921, Sukhbaatar was made commander-in-chief of the Mongolian Peoples Revolutionary Army, which defeated the Chinese again, and, later, the White Russians. In July of that year, he declared Mongolias independence from China at what is now known as Sukhbaatar Square.

He packed a lot in a short life; he died in 1923, at the age of 30. The exact cause of his death has never been known, and he did not live to see Mongolia proclaimed a republic.

Khorloogiyn Choibalsan

A great hero of the 1921 revolution, Khorloogiyn Choibalsan became Mongolias leader in 1928, probably purging or assassinating rivals in the process. Like his Russian mentor, Joseph Stalin, Choibalsan was ruthless. Following Stalins lead, Choibalsan ordered the seizure of land and herds which were then redistributed to peasants. In 1932, more than 700 people mostly monks were imprisoned or murdered, their property seized and collectivized. Farmers were forced to join cooperatives and private business was banned, Chinese and other foreign traders were expelled, and all transport was nationalized. The destruction of private enterprise without sufficient time to build up a working state sector had the same result in Mongolia as it did in the Soviet Union famine.

While Choibalsan moderated his economic policy during the 1930s, his campaign against religion was without mercy. In 1937, Choibalsan launched a reign of terror against the monasteries in which thousands of monks were arrested and executed. The antireligion campaign coincided with a bloody purge to eliminate rightist elements. It is believed that by 1939, some 27,000 people had been executed (3% of Mongolias population at that time), of whom 17,000 were monks.

Although Choibalsans regime has been heavily criticized by modern Mongolians, statues of him remain, and his name is still used for streets, cities and sums. Some Mongolians admire him for defending Mongolias independence.

|

|  |

|

|

|

|

THE SOCIETY AND ITS ENVIRONMENT

IN 1986 MONGOLIA CELEBRATED the sixty-fifth anniversary of the revolution that had begun the transformation of a traditional feudal society of pastoral nomads into a modern society of motorcycle-mounted shepherds and urban factory workers. The reshaping of Mongolian society reflected both strong guidance and a high level of economic assistance from the Soviet Union. The relations between Mongolia and the Soviet Union have been extremely close. The ruling Mongolian People's Revolutionary Party has so faithfully echoed the line of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union that some Western observers have doubted the reality of Mongolia's independence.

From Ulaanbaatar, however, issues of autonomy and the path of social development are seen differently. Of all the peoples of Inner Asia-- Uighurs, Uzbeks, Kirghiz, Tibetans, Tajiks, and others--only those in Mongolia retain any degree of independence. As a small nation of barely 2 million people, caught between two giant and sometimes antagonistic neighbors, China and the Soviet Union, Mongolia has had to accommodate itself to one or the other of those neighbors. Twice as many Mongols live outside the boundaries of Mongolia (3.4 million in China and .5 million in the Soviet Union), as live within it, and the fate of the larger Mongol population of China, who have become a 20 percent minority in the Nei Monggol Autonomous Region--once part of their own country--demonstrates that alternatives to the pro-Soviet alignment might well be less attractive. In the opinion of most Western observers, most Mongolians traditionally have tended to view the Soviet Union as a model of modern society, and the Russian language has been the vehicle for the introduction of science and modern technology and for contacts with the larger communist world.

Mongolia in 1921 was an exceptionally economically undeveloped society in which nomadic herders, illiterate and marginally involved in a market economy, constituted most of the population. They supported some petty nobles and a large number of Buddhist monks. The society's dominant institution was the Buddhist monastic system, which enrolled much of the adult male population as monks. Such limited commerce as existed was controlled by Chinese merchants, to whom the native nobility was heavily in debt. The only avenue of mobility and escape from broad and ill-defined obligations to hereditary overlords was provided by entrance to the Buddhist clergy, whose monks devoted themselves primarily to otherworldly and economically unproductive pursuits. The population appears to have been declining, because of high death rates from disease and poor nutrition, the large proportion of celibate monks, and high levels of infertility caused by venereal disease.

Against such a historical foundation, claims that contemporary Mongolia represents a completely new society are quite plausible. In many ways, the society has been transformed, and in the 1980s rapid social change continued. The ruling party saw the nation as having leaped directly from feudalism to socialism, bypassing the capitalist stage of development. Many of the forms of socialist organization, particularly in the rapidly growing urban and industrial sectors, appeared to be direct copies of Soviet models, with some modification to fit the Mongolian context. The population has nearly tripled since 1920, as the government pursued a pro-natal policy rare among developing nations. Mongolia's herds of livestock, which outnumbered the human population by at least ten-to-one, had been collectivized, and herders in the 1980s worked as members of pastoral collectives that drew up monthly and annual plans for milk and wool production.

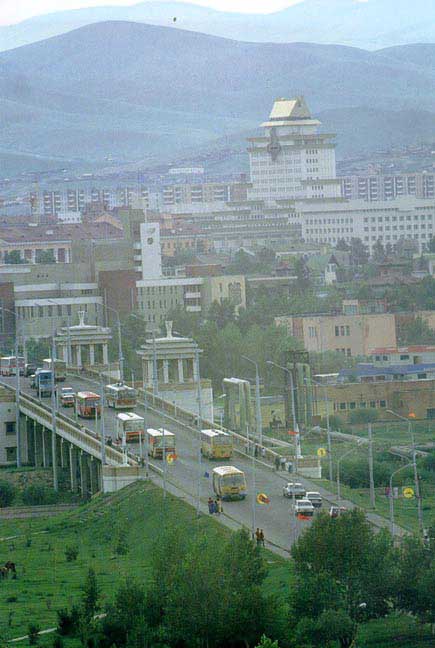

By 1985 a slim majority of Mongolia's population was urban, working in factories and mines, and increasingly housed in Soviet-model, prefabricated highrises. Public health and education had been the objects of intense development, which by the 1980s had produced vital rates approaching those of developed nations and nearly universal literacy among the younger generation. Much of Mongolia's industrial development and urban growth has taken place since the mid-1970s and has been so recent that the country was only beginning to recognize the problems attending rapid industrialization, urbanization, and occupational differentiation.

The drive for modernization along Soviet lines has been accompanied by an equally strong, but much less explicitly articulated, determination to maintain a distinctive Mongolian culture and to keep control of Mongolia's development in Mongolian hands. Although the topic was politically sensitive, Mongolia's leaders were nationalists as well as communists, and they aspired to much more independence than was permitted to the "national minorities" of the Soviet Union and China with whom the Mongolians otherwise had so much in common.

|

|

|

|