By L. Badamkhand

As any other nation, Mongols do have a distinctive national character. It is not an easy task to describe all its features as drastic economic and political changes took place within the last century alone, each time introducing new values and habits, traditions and morals. From a purely Buddhist country at the turn of the 20th century, Mongolia jumped into socialism, bypassing capitalism as a popular slogan coined in communist times says. Now, Mongolia painfully steps back into capitalism. These political transformations contributed into twisting the traditional core moras and shaping the habits and attitudes of Modern Mongols.

So it is rather hard to pinpoint something specific as each generation has an imprint of its time, and this description outlines only the basic archetype, preserved over centuries of turbulent history of Mongolian nomads. A lone gher lost amidst vast open stretches of steppe always surprises visitors to this country. Independent life in nearly total wilderness where one can rely only on its own has shaped the self-reliant and rugged individuality of Mongols. However, not egoism as Mongols are always ready to help others.

Another feature that strikes foreign visitors surprise is the drastic contrast between urban and rural people. While city folks enjoy almost all the benefits of civilization and look more than European, the rural population still lives nomadic lifestyle following herds and worshipping the nature. The revolutions, political upheavals and economic reforms have had little impact on nomads still living simple life short of many modern goods and services. But what they lack in terms of materialistic life is more than compensated by the richness of the nomadic culture, moral values and traditions that comprise the backbone of the true nomadic spirit.

Hospitality

Under the nomadic traditions it is a duty to welcome and treat any visitor with a cup of hot tea, offer a plate with cheese, fresh cream, some curds and candies. Only after this, a host will inquire politely where the guest comes from and where goes to. If the guest is not in hurry, he or she will be given food and provided with a bed to sleep on. On the guests side it is customary to, at least, step into a gher, to try the offered tea and food, before starting any conversation.

The description of Middle Age travelers that it is possible to travel across the country without spending a single penny still holds truth. Nowadays, after a decade of transition to market economy, one will rarely be asked to pay because it is considered shameful to ask money for hospitality. In case, the guest wants to show appreciation, a small gift, some candies for kids will do.

Even the city folks still remember this tradition, and wont be surprised if your Mongolian friend shows up at your door without any warning or invitation. This is just the custom. Up to now, the tradition of greeting a passing by caravan with a jug of freshly brewed milk tea is being observed. This is the unwritten rule of the nomadic way for Mongols know what is the struggle for survival and the value of timely help.

Openness

Wont be surprised either if a Mongolian you just met on a street invites you to his/her home. Mongols are basically very friendly people, and easily find a common language with others. They will ask you where are you from and where are you going. This is not a simple curiosity because in vast open steppes, human communication and new information it brings in are scarce commodity. If you accept the invitation and go in, be prepared to see a stream of the hosts neighbors, relatives or others who simply walk in and sit at a table, listening and watching. This is a peculiarity of Mongols who are more open than any other Asian nation and appreciate the value of meeting new people and learning new things.

Adaptation skill

Mongols are used to the extreme changes of temperature, sudden natural calamities and become highly adaptable to any climate, perhaps, except humid one. This also applies to different cultural settings and environments. Open for new ideas and information, Mongols easily learn new social norms, but also quickly abandon them in new conditions. The history shows that Mongols easily adapt to new conditions but never accept them as a rigid norm. Perhaps, the ever-changing life of wandering nomads, as well as the flexibility of mind necessary in changing situations explains this feature.

Reserved emotions

At first sight, Mongols seem to be very reserved showing no trace of emotions or feelings. But this is not true, just that open expression of feelings as well as quick judgements are traditionally considered to be improper, while patience, sound judgement and acceptance are valued. Shifting emotions and tempers are sinful, while understanding is a good deed, said elder Mongolians interview some 20 years ago by a team of Polish ethnographers.

Helpfulness

Mongolians are always willing to help. The life in a large, sparsely populated country where nomad families stay some 50 -100 km from each other formed two distinctive features. One is individualism, which means reliance on own skills and knowledge to survive through natural calamities or other tests. And the another is the readiness to help others. If one herder family loses all their animals, relatives and neighbors will dutifully donate a sheep or a cow to recover. If there is a problem, so will be people willing to help. This tradition is rather being abandoned in cities, where it took the form of markers - I help you, you help me next time.

Stamina and patience

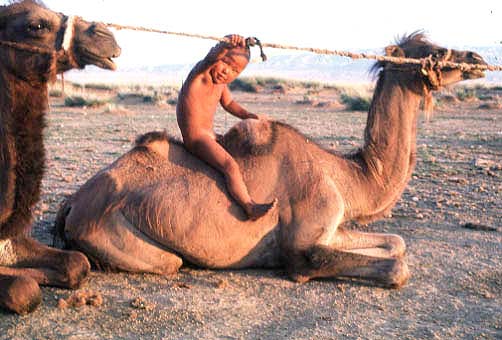

These qualities without which the nomadic life is simply impossible, are being instilled from the very childhood. By the age of 12-13 teenagers are fully capable to tend herds, to look after the household. So, if one says that he/she was born and grew up in steppes mean that the person has undergone a thorough training to be a self reliant and self confident individual able to endure hardships and life tests.

But there are many other features of the national character of Mongols that also may surprise foreign visitors.

Addition to alcohol

Each and every Mongol drinks, consuming about 12 liters of alcohol per capita, from the very top to very down, male and female. Drinking become a custom, and it is hard to believe that 30 years ago Mongols were almost all but abstinent.

Ever since Chinggis Khaan times, drinking alcohol was strongly discouraged, and only matured elders over 36 were allowed to drink at their will, and even in that case, only a mild, 13-15 % proof beverage made of distilled milk was available. Historical records left a description of a civil unrest back in 13th century when enraged residents of Khar Horum, the capital city gathered at the doors of the Khaan Palace demanding to close a wine store run by a foreigner.

Seven centuries later, under the faltering socialist economy short of goods and services, the new rulers found a way to collect back wages given to workers. In 1959 the first distillery producing vodka was built, and a heavy public relation campaign praising modest consumption of alcohol launched. Mongolian Youth League members traveled for months all across the country, promoting the benefits of drinking alcohol. Well, the task was fulfilled and the state coffers again swelled along with the climbing number of drinking people. Mongols do drink, and unfortunately it turns into a national trait. Scientific research showed that Mongols lack a blood ferment that disintegrates alcohol, and for this reason, Mongols get drunk easily losing any control. As much as 80% of all crimes are being committed while drunken.

But even now, the tradition of abstinence holds, and it is considered impolite to press guests to drink more than three times. And for foreigners, it is fine to just taste the offered drink and give it back.

No punctuality, poor organization

There and here, all foreign visitors will, unavoidably, face these. But no need to waste nerves and try to change things. At the last moment things will work out, and all problems solved. Not that Mongols are lazy, it is just they used to spontaneous reaction towards changing situations and conditions, a trait developed over centuries of living in a highly unsteady natural environment where sand storms or snow avalanches come without any warning, or rains turn into floods and summer heat results in a drought. Flexibility and the ability to act under pressing situations, to mobilize all resources - these are the key to survival of nomadic herdsmen.

Free wandering over the vast open steppe stretches following the natural cycles dictated different from settled nations' perceptions of time and space. And though with the advance of market economy the pace of life speeded up, the punctuality and the sense of deadlines are still have not become a social norm. Space also has different meaning for nomads limited not with house walls but the horizon only. If you are told that it is close enough, be ready to drive for many more kilometers before reaching the destination.

Socialist mentality

Mongols as any other former socialist nations have the hangover of the Homo Sovieticus mentality common for people who lived for decades under totalitarian regimes. Do not complain if a bathtub is not working or a lamp is not switching on. Or if you are not promptly served. These are the legacy of times when everything belonged to the state or to nobody, and when quantity and fulfillment of plans was more important than the quality.

Sanitary and hygiene

Do not expect European standards, especially in rural areas. The resources are scarce and far from meeting the standards, especially hygienic ones. In past, Mongols were always carrying along a personal cup and sticks for food. Therefore, it is better to take along all the basic necessities, toilet paper including.

Theft and robbery

These crimes, very rare before, become common as the economic crisis took its toll in the form of mass unemployment and impoverishment during the last decade of the transition to market economy. Usually foreign visitors commanded deep respect, but even this is eroding with the number of foreign victims increasing each year. The best way of avoiding such crimes are well known: watch out when in crowded public places, walk not late night, or carry large amounts of cash in pockets, ask for documents or identification when approached by police officer or strangers.

Finally, be patient. Each nation has its customs, with different set of cultural traditions and ways of life. For example, it will never occur to a Mongol to knock at door and ask permission before entering a room. For centuries, the homes of nomads were always open for any guest and their life was simple enough, with no need to hide anything. So do not be angry or quick to judge. It is better to understand and accept as each one of us has own customs and ideas.

|